The life story of Stacy Melle is one of mind and spirit triumphing over circumstances.

By Nancy Matsumoto

As a child being treated for cystic fibrosis (CF), she didn’t know exactly what she was suffering from, but she saw her friends around her at the hospital clinic succumbing, one after another. Her parents, worried about the effects this disturbing environment might have on her, had her transferred from her hospital in Palo Alto to another one in San Francisco. “Kids were passing away all the time and that’s not an easy thing to watch or observe,” recalls her mother Ann Hawes.

When she was about eight, Stacy asked her mother, “Mama, am I going to die?” Her mother answered, “Oh, yes honey, we all are, we just don’t know when!” Stacy thought about this quietly, and seemed to internalize her mother’s answer. When she was fourteen, she happened to read her doctor’s notes and learned the name of the disease she had been diagnosed with at age two. She also learned that the average life expectancy of pediatric CF patients at the time was 18 years.

But Stacy confounded all expectations. She did it with such ease and grace that many of her friends never knew of the epic battle she fought on a daily basis, how the odds had been stacked against her almost from birth. And because she understood that life is precious, she squeezed more joy from each day than those of us who forget how fleeting it is.

Stacy was a perfectionist and super-achiever from the beginning, creating a meticulously detailed “secret code” when she was 10, a prize-winning illustrated story book when she was 11, and penning wedding invitations in her beautiful calligraphic script by the time she was 12.

She was a top student, a high school cheerleader and president of her college sorority—even though she didn’t have the physical stamina to walk across campus. She knew exactly where she was going and put in the work to achieve her goals. She found professional success and satisfaction as a trailblazing woman in a profession dominated by men.

It didn’t matter that Stacy had to spend every Christmas vacation in the hospital, having her lungs cleared while her classmates and friends played. It was just what she did: have an early supper with her parents and her brother Jason, play games and have fun. She had no time for complaining. She found the love of her life in her husband Kelly, with whom she shared twenty years of the kind of deep, unconditional love that too few get to experience in life. When Stacy and Kelly met in Los Angeles on New Year’s Eve 1997, Kelly had no idea Stacy was anything other than the vibrant, glowing young woman she appeared to be. At a party at the former Chasen’s restaurant, they were drawn to each other. For Kelly, it was love at first sight. They kissed on the dance floor and again at midnight. They shared greasy grilled cheese sandwiches afterward at Norm’s on La Cienega. They went on three whirlwind dates, and then Kelly got a call: Stacy had flown north and was in Stanford Hospital about to receive a double lung transplant. Such a shock would have sent most men running for safer shores. But not Kelly. “There was no hesitation,” he recalls. “I found her beautiful and full of life. I really admired her. How hard she worked, her perseverance, how positive she was.” He was 30, and she was 29.

Post-transplant, Stacy was so immuno-compromised that live flowers were not allowed in her hospital room. Instead, Kelly sent her a crystal orchid, a symbol of his love and commitment. He had only known her for five weeks.

During her recovery, Stacy and her mother stayed in a small apartment several blocks away from the Stanford Hospital. “I would make her walk up and down the stairs, and we’d sing ‘You Are My Sunshine’ all the way to the hospital and all the way back to help strengthen her lungs,” recalls Ann. The two were so close that after Stacy left home and moved to LA, they would check in by telephone several times a day to share a laugh and the day’s news. When Ann confessed she was at McDonald’s having lunch—a place officially deemed unhealthy and off limits—Stacy promised not to spill the beans.

Stacy and Kelly married in August 1999 in her home town of Los Gatos. Reveling in her new lung capacity, they traveled the world. Father Paul Soukup, Stacy’s communications professor at Santa Clara University and the priest who married them, recalls her telling him, “I can finally ride a bicycle!” Suddenly, activities others took for granted were within Stacy’s reach. She and Kelly visited 19 states and 20 countries, adventures that Stacy stored in memory and in her meticulously crafted photo scrapbooks.

A Champion at Coping, a Career in Cable Television

Stacy always knew how to cope. She was only about five or six, her mother recalls, but “when she’d get upset with us, she would put on her jacket and coat, and put a little hat on her head. She’d take her lunchbox filled with all her treasures and walk out of the house and around the corner. We lived on the corner, so we could see her plop herself down.” Ann and her husband Bill could hear their daughter animatedly airing all of her grievances to an invisible companion. “Then, all of a sudden, she would come back home and everything was okay,” recalls Ann. “Looking back on it, that was her whole life. She did what she wanted to do and needed to do, and she kept it very private.”

This is why, throughout most of her life, even Stacy’s close friends had no idea that she battled a debilitating disease every day of her life. Holly Leff-Pressman, a friend of Stacy’s who had left their workplace at Viewer’s Choice in 1994 to take a job with NBC-Universal, recalls working with Stacy in the early days of cable: pay-per-view, video-on-demand, and then direct-to-consumer streaming. “It was a very scrappy business in the early days, and we were pioneers,” she recalls. “We had really fun times and Stacy had a great attitude.” It was also a business dominated by men in which women had to work twice as hard. There was no leeway to become sick or show vulnerability. Stacy served as an affiliate relations manager at Viewer’s Choice and let Leff-Pressman know she was interested in a position at NBC-Universal.

When a job opened up for her number two in command, Leff-Pressman says, “Stacy was my first call.” Stacy responded that she was interested in the job, and the two began to discuss the details. At some point, Stacy said, “I just have this little thing going on—I’m going to have a lung transplant.”

“I’d known her all these years, and I had no idea,” recalls Leff-Pressman.

Six months after her transplant, Stacy began working at NBC-Universal. Over her nearly 15 years there, she rose to the position of vice president of marketing, collecting a number of awards and accolades along the way. One of them was inclusion on The Hollywood Reporter’s list of “35 executives poised to become industry leaders.”

“If you didn’t have two arms and a leg tied behind your back because of CF,” Kelly would tell her, “You would be running a studio or a studio division.” Leff-Pressman says, “She did it with such grace. She kept working, and she wanted to get promoted. I’ll never forget I had a friend who terminated a pregnancy when she found out the baby had a gene for cystic fibrosis. I had a dream about Stacy that night and woke thinking, ‘Oh my God, Stacy wouldn’t be here (if her parents had made that choice).”

But to her parents and brother, Stacy was a miracle and a blessing. Her mother Ann says, “She was God’s gift—that was Stacy Melle.”

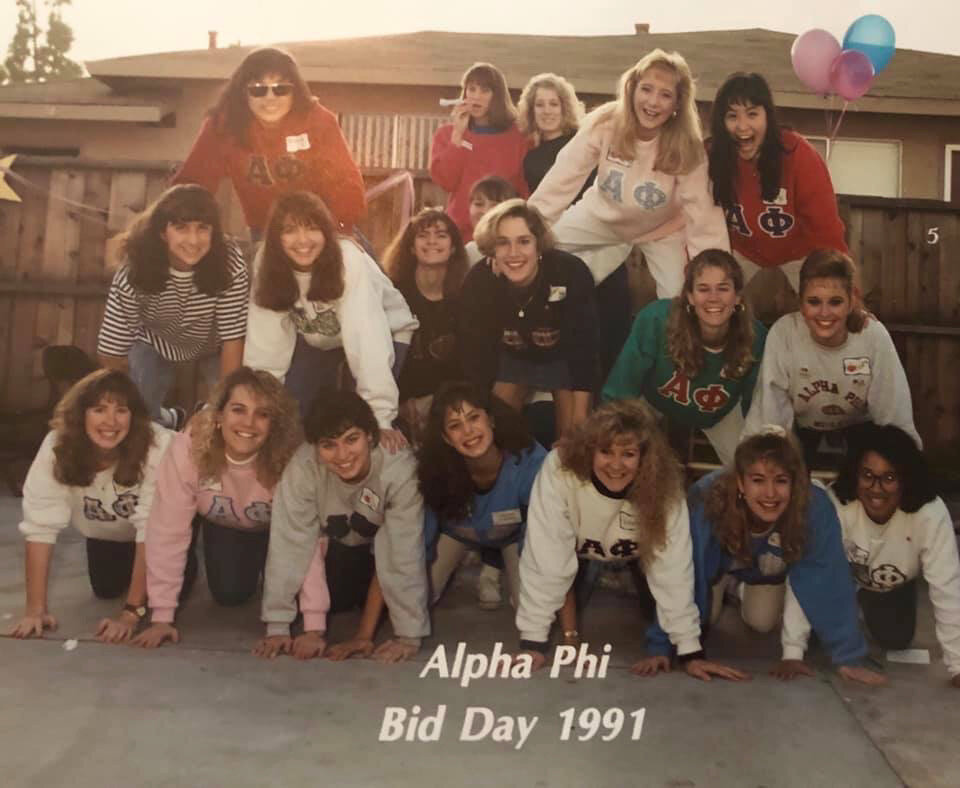

Stacy’s 1988 Alpha Phi sorority pledge sister Sacha Basho says, “She had a thirst for life and was an amazing role model. Stacy always had her hand in all sort of things. She was super social, a flirt, she had a curiosity about people that was very engaging, always with a big smile. She brought this very festive spirit with her, and you could see how loyal she was to long-term friends, many who go back to grade school and high school.” Her talent for friendship made her “wonderfully attentive,” recalls Father Soukup. During one Christmas visit, Stacy gave him a special hot chocolate blend that she remembered him ordering during a previous visit, something even he hadn’t remembered doing.

Basho also recalls Stacy’s exceptional work ethic. She was organized, determined and decisive, with a clear vision of what her finished product would look like. She put in the extra time to make that vision a reality, but would never reveal what it took to get the task done. She made it look easy. In addition to being president of her sorority, Stacy and her sorority sisters led their class; their junior year, Stacy’s friend Kara was president, Stacy was vice president and Basho was treasurer.

Because they had shared the intense bonding experience of pledging together, Stacy’s sorority sisters were among the small group of friends who knew of her chronic condition. You almost had to ask yourself, if Stacy can get up and do it every day, what’s my excuse?” Basho says.

Lung Transplantation: Still Defying Expectations

The lifespan of the average patient following a lung transplant is from two to three years. Although patients are closely monitored for the first three months after surgery, Stacy suffered complications, chronic rejection on one drug, and then serious side effects on the replacement drug. But she survived them all, living ten times longer than the statistical average.

Yet by 2012, Stacy’s health was fragile enough that her doctor and family worried that a planned African safari would be too much for her. Her UCLA pulmonologist, John Belperio, M.D., told her, “On paper, you absolutely should not go. But knowing you, and what you’re capable of, it’s a perfect time to go—enjoy it.” She and Kelly “got great gratification from it, a huge, nine-month bounce,” he recalls. “Stacy was just invincible, and she would always win the mental battle, she had that gift.”

When travel was no longer an option, Stacy and Kelly had dinner parties at their home and explored LA restaurants. By 2013 Stacy was losing kidney function and suffering from lymphedema, the accumulation of fluid in her legs that was a side effect of one of the immunosuppressive drugs she was on. The swelling led to painful bacterial infections and even sceptic shock. Still, Stacy was determined to keep working; she loved her job. Compression garments allowed her to do so for a while. “Her life was work and taking care of her health,” Kelly recalls. He made the up-to-two-hour drive from their home in Stevenson Ranch to drop her off at work and pick her up every day, did the cooking, and took care of the other mundane chores of life, all while holding down a demanding job in financial services. Stacy’s determination to maintain her career as long as possible was so strong that before what would be her last business trip, Kelly recalls, “She had me buy an extra suitcase so she could pack the whole lymphedema outfit and take it with her to New York.”

Her hospitalizations for various issues, ranging from pneumonia to bowel blockage to sinus surgery and a broken rib (all caused by her chronic illness and transplantation issues), began to increase. Between 2012 and the end of her life in 2019, Stacy was hospitalized 50 times for a total of 373 days. “She would be in the hospital one day, and look like she was going to die,” recalls Dr. Belperio. Then I’d walk in on day two, and she would be right on her computer, getting to work, really, just trying to fulfill her own dreams.”

Throughout all of this Kelly and Stacy squeezed in as many fun adventures as possible. I’m amazed at how much we still did,” Kelly recalls, “given Stacy’s health. We took any opportunity, bought anything we needed to make it happen.”

When she was no longer able to work, the couple adjusted once again. They’d take road trips to see family in Phoenix and Los Gatos, Stacy stretched out in the back seat with her iPad, wearing her Beats headphones, catching up on episodes of “The Voice,” or “The Real Housewives.” Resting in her leather armchair at home, she was surrounded by symbols of family, travel and love: the floral painting by her grandmother, a church pew her parents had brought home from Germany, and a glass-fronted cabinet filled with collectibles she and Kelly had brought home from their travels. Her caregiver Nora would fix her lunch, and Kelly would make dinner.

“She would create these tangible goals to keep her going, and her goals changed over time,” recalls Dr. Belperio: instead of going hiking again, her goal over time became being able to climb a set of stairs.

“We just managed,” Kelly says of those years. During one hospitalization, he wrote a report presenting the results of a forensic investigation into a multi-million dollar transaction while sitting in the emergency room at UCLA hospital, then kept Stacy company in her room, sitting in the space between her bed and that of a patient suffering from an opioid addiction. Every night, he would drive from his office in Century City to the hospital, and on weekends he worked from her room. Through it all Stacy stayed positive. When she was feeling up to it, Kelly would take out dinner from a good restaurant. “We’d just enjoy that, and watch a television show,” he says.

Turning 50

In February of 2019, Stacy turned 50. That month and throughout the year, there were joyful 50th birthday parties for her and for her friends. The last one took place in Las Vegas the weekend before Stacy left this world, complete with a stop at one of Stacy’s favorite fast food restaurants, Arby’s.

Stacy and Kelly had weathered so many health crises that, as Dr. Belperio says, “You really began to feel that Stacy was invincible.” So when Kelly took her to UCLA emergency room in October of 2019, he assumed she would miraculously bounce back.

“She had gone into sceptic shock a dozen times and she always came out,” Dr. Belperio says. “This time she didn’t.” The end came quickly. “She literally enjoyed life until the day she died,” her doctor recalls. “There are certain times when it’s a privilege to deal with a patient and to be their doctor. This was true of Stacy and Kelly both. The love between Kelly and Stacy was synergistic, it really brought her to another level.”

“I was a young man when I met Stacy and I learned what true love is from her,” Kelly later wrote. “She taught me how to make the best of my shortcomings based on how she handled her disabilities. I am the man I am today because of her and I will forever love her for handling her many issues with grace and confidence.”

Buried with Stacy is a card from Kelly that reads, “Thank you for our beautiful marriage. I love you. Kelly.”

Portrait by artist Jeremy Sutton contains a collage of 14 images reflecting Stacy’s life including her calligraphy, a code language she created for a school project, an image of her as a child, a crystal orchid given to her by her husband when she received her double lung transplant, a bride, her and husband as newlyweds, her in Spain on her honeymoon, a Lifetime Achievement Award she received from an entertainment industry association, her favorite gummy bear candy, her favorite Minion movie character, her career at NBCUniversal, her favorite Hollywood Bowl concert venue, a globe representing her love of travel, and her favorite restaurant Nouveau Cafe Blanc.

Stacy Ann (Hawes) Melle

February 18, 1969 to October 10, 2019

Laid to Rest Madronia Cemetery Saratoga, California

Please consider a contribution to the following endowments in Stacy’s memory:

Stacy Ann (Hawes) Melle Scholarship at Santa Clara University

Lung Health Research Accelerator at UCLA

Words of Remembrance

by Neel Chatterjee

UCLA Lung Health Research Speech

November 8, 2022

by Kelly Melle

Stacy A. Melle Scholarship

2025 Santa Clara University

Maggie Curtis

B.A. Communication

Stacy A. Melle Scholarship

2025 Santa Clara University

Karla Hernandez

B.A. Communication

Stacy A. Melle Scholarship

2025 Arizona State University

Arely Castillo

B.S. Biological Sciences